School of Global Policy and Strategy Study Room

International expansion can happen almost by accident–if you're a consumer Internet company, you get offered a deal by a big German partner, or if you're an enterprise software company, your sales guys sign a bluebird deal in Japan to make the quarter–but that rarely turns out well. The markets you end up in turn out to have limited potential, or the cost to serve them turns out to be a lot greater than you thought. Customer commitments get missed, or tensions arise between the sales guys who sold the deal and the product people who weren't involved but now have to deliver it. All of a sudden, international expansion has a bad name.

It doesn't have to be like that. On the contrary, going global can be highly rewarding for everyone if it's deliberate and strategic. Before you make your first move overseas, you should have an explicit, well-communicated, company-wide international strategy that will act as the company's "True North" as it crosses the border.

Five key questions

Your strategy should address:

- What's our goal?

- What countries will we focus on?

- With what product(s)?

- How will we go to market?

- What's our operating model?

Let's talk about each in turn:

1. What's our goal?

This can be a qualitative statement such as "Be the number 1 player in mobile gaming in the top 5 world markets by 2014", or a quantitative target such as "Generate 50% of our revenue from outside the U.S. by 2016"–or a combination of both. It should be big, specific and measurable, because it will set the bar for the rest of the strategy.

2. What countries?

What countries to focus on, and in what order, is perhaps your most important decision. Many U.S. companies launch in the U.K. next, because they speak English and it feels familiar–but is that the next best market for you? Every new country you enter will require an investment of precious time and money, and will generate a certain return. In simple terms, you want to prioritize countries offering the most return for the least investment.

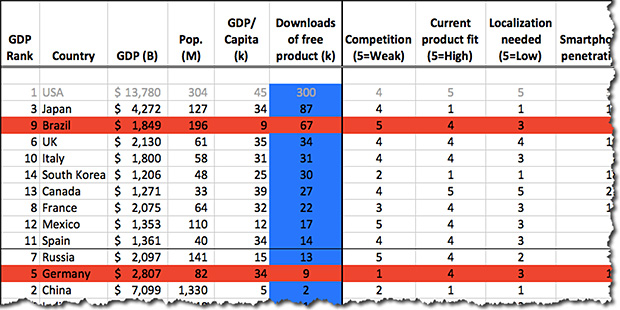

That should start with a quantitative, data-driven analysis (aka a spreadsheet!), ranking the world's countries according to the criteria that define an attractive market for you.

Those should include both Macro criteria related to overall market size–such as Population; GDP per Capita; Internet penetration; Broadband penetration; Smartphone penetration; 3G deployment–as well as Company-specific criteria. If you're an enterprise software company targeting financial services giants, then "Number of banks with over $XB in assets" would be a highly relevant criterion. For our data center automation company, Opsware, it was Number of servers or Network devices. Sometimes fairly arcane factors can make one market much more attractive than another: When I was running @Home International, Availability of two-way cable networks for broadband Internet services made markets like Australia and Netherlands more attractive than much larger countries like Germany. Competition will almost certainly be a criterion, as will Product fit: Your product may work with minimal changes in some countries, while requiring months of development work for others.

This is real work, but it's a hugely helpful exercise, because it forces everyone involved to think through what makes an attractive market, in terms of both potential and the investment required to realize it. When you're done, you should have a ranked top 20 list that will both guide your proactive expansion and give you a fact-based framework to react to opportunities that pop up along the way.

Naturally, analysis doesn't take the place of judgment–it just supplements it. You may decide to postpone entry into a market that looks good on the spreadsheet because you believe the company isn't ready or the risk is too high. For example, China might look very attractive on the numbers, but concerns about IP protection or ability to enforce contracts might well deter you.

3. What products?

Obviously, you need product requirements and a product plan for every market you're going to enter. Unless you're lucky enough to have a product like Twitter that works pretty much the same everywhere, that means product management and engineering work, and additional resources to be assigned to getting it done.

4. How will we go to market in each of the top 3-5 countries?

Another question with major ramifications. If you're a mobile app company, maybe a partnership with a mobile operator is the way to go. If an enterprise company, will you need to hire a direct sales force or can you start with a channel partner? If you have a freemium model like Box.Net or Splunk, maybe you can seed the top 10 countries by promoting free downloads and then target the most successful ones with direct sales.

If local clones have got there before you (as in Groupon's case) you have a build/buy decision to make: Acquiring a local competitor buys you instant market position and a team, but technology that may be hard to integrate and a team you didn't hire, with values that you may not share.

While every situation is different, and there's no one right answer, I would generally beware of relying excessively on a partner, and particularly try to avoid joint ventures–more on that another time!

5. What's our operating model?

In the rush to launch overseas, this is often the most overlooked question. The core decision you need to make is which functions you're going to manage centrally, and which locally. For example, if a shared global technology platform is a fundamental competitive advantage (as it is for Google, Facebook, Zynga, or Airbnb), then that's one area where you don't want to give local autonomy. In its early years, Yahoo! gave its individual European country teams virtually free rein to develop local versions, leading to a wasteful hodge-podge of inconsistent platforms, petty fiefdoms and internal infighting between European and corporate executives.

Source: Campaign UK, February 19, 2001

While Google powered ahead with a common technology platform and a clear command structure, Yahoo! Europe never recovered from this failure to pick the right operating model. Read between the lines of this extract from Carol Bartz's February 2009 reorg memo:

Operating model decisions drive organization structure decisions: In most cases, a matrixed structure will ultimately provide the best combination of centralized consistency and efficiency with localized customization and execution: Local team members reporting dotted-line to a local GM and hard-line to their corporate function (or vice-versa). The org structure will need to change over time as the international business grows in size and complexity. At the beginning, you should optimize for low overhead and rapid execution, but with enough corporate legal and finance oversight to minimize the risk of bad tax or IP decisions, or worse, fraud or FCPAviolations.

Wait–that's a lot of work!

By now you're undoubtedly thinking: I'm already working 16 hours a day, and so is my team–who's going to do all of this new work? As the CEO, your role is to sponsor the work and assign someone passionate, credible and independent to lead it. I'll talk about that in my next post.

Up next: Assigning ownership and ensuring commitment.

John O'Farrell is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz. John led the firm's investments in Facebook, Twitter, and Groupon, and works with portfolio companies on partnering, strategic transactions and global expansion. John has an MBA from the Stanford Graduate School of Business and a Bachelor of Electronic Engineering from University College Dublin. He speaks English, German, French, and Portuguese.

School of Global Policy and Strategy Study Room

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/1767803/get-yourself-global-strategy

0 Response to "School of Global Policy and Strategy Study Room"

Post a Comment